Large Language Models and Scientific Writing (Part 1)

In the past weeks, I had the opportunity to give two talks on working scientifically (in Bielefeld on Open Science and Cologne on Reproducibility). Naturally, large language models (LLMs) and the influence they have came up as a topic in both. Because I did quite a bit of research, I thought it would be good to share the key insights in this form as well. This is the first of a (small) series of posts.

Scientific writing has changed in a measurable way since ChatGPT has launched

Everyone who is involved in examinations these days knows how hard it is to actually determine whether something has been written by an LLM, and the same applies to scientific texts.

Let’s start with evidence that has been found either by accident or by very simple means: This mastodon-post was made by John Mark Ockerbloom in March 2025, and it describes the finding of something interesting in the book “Advanced Nanovaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy”, published (and sold) by Springer, with ISBN, DOI and everything. Page 25 contains the following:

1.6.3 Why Cancer Vaccines Are Better than Chemotherapy

Cancer vaccines and chemotherapy are two different approaches to treating cancer, and their effectiveness can vary depending on the type and stage of cancer, as well as individual patient factors. It is important to note that as an Al language model, I can provide a general perspective, but you should consult with medical professionals for personalized advice.

Springer has taken it offline (without any information, thus also ‘breaking’ the idea of DOIs), but Amazon.de still sells the 1-star-reviewed book for 171€.

In a similar vein (but about one year earlier), Elen Le Foll, a colleague at the University of Cologne, found a lot of articles on Google Scholar that contain phrases like “I am an AI language model”. – and several other people joined in. Examples she reported on Mastodon are (as far as I can tell) from medicine, bio-science in general, and computer science. Some of the mentioned/linked articles have been transparently removed in the meantime, others have not.

With the same method, but a bit more systematically, Haider et al. (2024) looked for key phrases showing LLM use on Google Scholar. These key phrases are “as of my last knowledge update” and/or “I don’t have access to real-time data”, which can be considered dead giveaways for LLM use. Except for the use in example sentences discussing LLM use, I cannot imagine a context in which these would occur naturally in a scientific article. They investivate publication venue and scientific fields of the found publications:

Most questionable papers we found were in non-indexed journals or were working papers, but we did also find some in established journals, publications, conferences, and repositories. We found a total of 139 papers with a suspected deceptive use of ChatGPT or similar LLM applications […]. Out of these, 19 were in indexed journals, 89 were in non-indexed journals, 19 were student papers found in university databases, and 12 were working papers (mostly in preprint databases).

The queries on Google Scholar were not restricted to any particular scientific field, and the questionable papers were majorly assigned to three areas: health (14.5%), environment (19.5%) and computing (23%). What the authors also point out is that these are “policy-relevant” subjects, which gives rise to the possibility of automatically creating a lot of pseudo-scientific articles to give, for instance, the false impression that some topic is under debate (think: climate change). Obviously, looking for these key phrases works with high precision, but doesn’t detect a lot of the generated text.

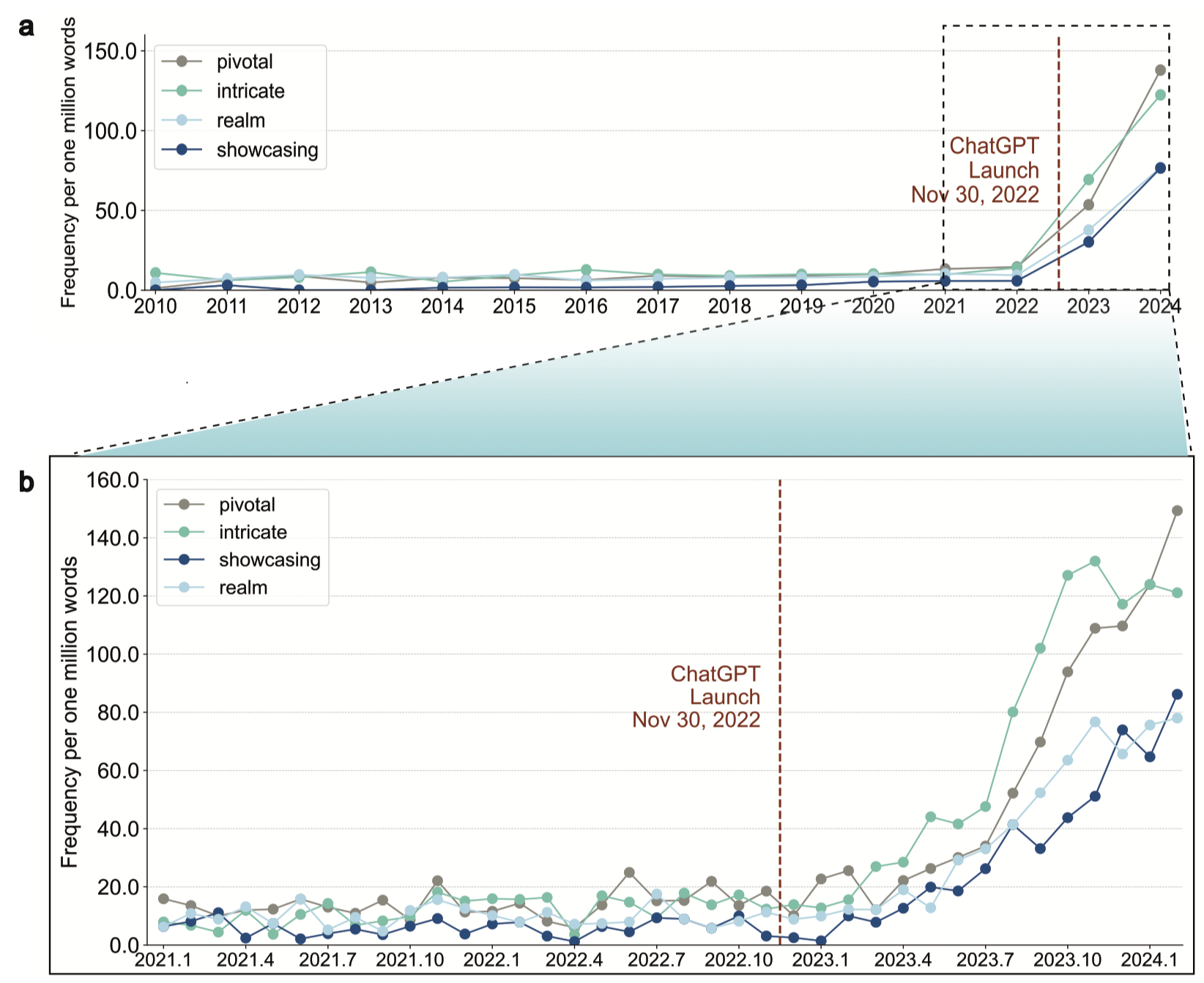

Another take on this problem is the paper by Liang et al. (2024): They investigate 950,965 papers that have been published between January 2020 and February 2024 on the preprint servers arXiv, bioRxiv, and in Nature journals. In the abstracts of the papers, they find that the words “intricate”, “pivotal”, “realm” and “showcasing” have become much more popular since the launch of ChatGPT (although with some delay). The resulting picture (Figure 2 in the paper, and small on the left) is pretty clear: While this is “just a correlation”, all the other factors that I can imagine that could be in play here would lead to a much higher fluctuation of the popularity of these words before the launch. But of course, these could also be the result of people using ChatGPT to improve their writing.

Another take on this problem is the paper by Liang et al. (2024): They investigate 950,965 papers that have been published between January 2020 and February 2024 on the preprint servers arXiv, bioRxiv, and in Nature journals. In the abstracts of the papers, they find that the words “intricate”, “pivotal”, “realm” and “showcasing” have become much more popular since the launch of ChatGPT (although with some delay). The resulting picture (Figure 2 in the paper, and small on the left) is pretty clear: While this is “just a correlation”, all the other factors that I can imagine that could be in play here would lead to a much higher fluctuation of the popularity of these words before the launch. But of course, these could also be the result of people using ChatGPT to improve their writing.

Liang et al. (2024) continue to apply a measurement method to estimate the portion of “LLM-modified sentences” on the same corpus (limited to abstracts and introductions). The measurement method is basically an maximum likelihood-estimation model that has been trained on gold standard documents. According to this analysis, between 5 and 17.5% of the sentences in the abstracts have been LLM-modified, depending on the discipline. The number is highest in computer science and lowest in math, and has been steadily increasing since early 2023. Figure 1 in their paper shows abstracts, Figure 6 introductions – the findings are roughly the same.

The most important thing to note here is that Liang et al. investigated sentences, and not articles. I.e.: The portion of LLM-generated articles is not estimated here. It seems plausible that the portion of LLM-generated sentences in some abstracts and introductions is higher, while being lower (for instance, zero) in others. In the extreme form (and positive interpretation), this could even mean that the actual number of researchers that “let articles write by an LLM” is very low. But we do not know exactly.

All this is not very surprising: Researchers are humans and under a lot of pressure, and any method that makes publishing faster and thus publications lists longer will be used, until we come up with a better method to measure and compare scientific success(es).

Next: LLMs and Peer Review.

References

Elen Le Foll. 2024. ‘I Just Did Some Primary-School Level Investigative Work’, 15 March 2024. https://fediscience.org/@ElenLeFoll/112101278590379648.

Haider, Jutta, Kristofer Rolf Söderström, Björn Ekström, and Malte Rödl. 2024. ‘GPT-Fabricated Scientific Papers on Google Scholar: Key Features, Spread, and Implications for Preempting Evidence Manipulation’. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, September. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-156.

John Mark Ockerbloom. 2025. ‘Our Library Has Access to a Book Published By …’, 24 March 2025. https://mastodon.social/@JMarkOckerbloom/114217609254949527.

Liang, Weixin, Yaohui Zhang, Zhengxuan Wu, Haley Lepp, Wenlong Ji, Xuandong Zhao, Hancheng Cao, et al. 2024. ‘Mapping the Increasing Use of LLMs in Scientific Papers’. In First Conference on Language Modeling. https://openreview.net/forum?id=YX7QnhxESU.

Thorat, Nanasaheb. 2025. Advanced Nanovaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy: Harnessing Nanotechnology for Anti-Cancer Immunity. 1st ed. 2025. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-86185-7.